MINOR SPOILERS

After watching The Post, I realised something about director Steven Spielberg’s recent dramatic work: its style feels dated and kind of out of touch. Now don’t get me wrong, I found Bridge of Spies, Lincoln and War Horse to be decent, well-crafted films, but they didn’t captivate me like his older stuff did.

Spielberg’s drama comes in two forms: the first is a darker, grittier and more realistic approach used in films like Munich, Schindler’s List and Empire of the Sun. The majority of his dramas use a second approach that’s more hokey and melodramatic. It’s no coincidence those films tend to also be patriotic in flavour: Lincoln, Amistad and Saving Private Ryan are good examples. I’ve never been a big fan of this sometimes irritatingly naïve style, which is abundantly used by latter-career Spielberg.

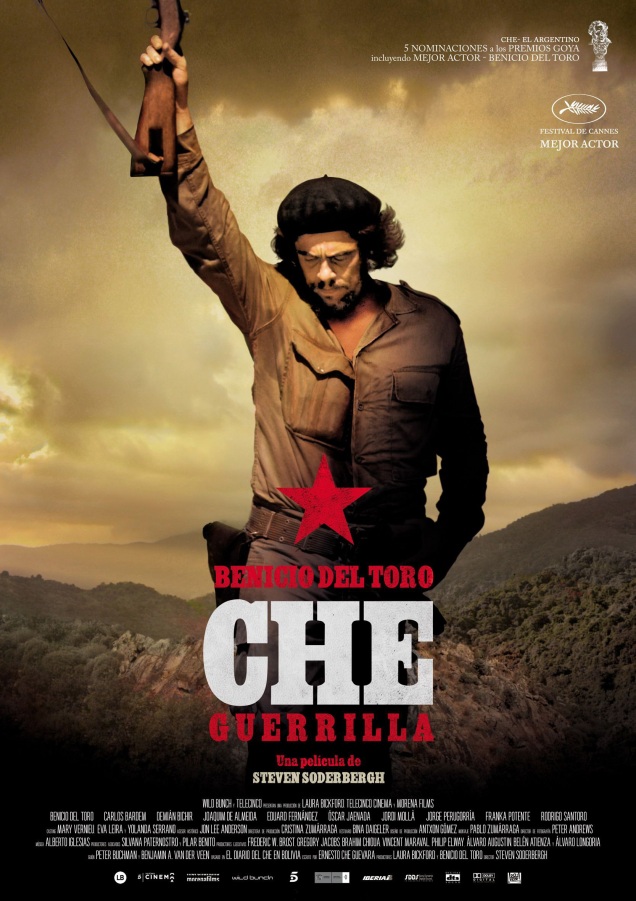

The Post, his latest endeavour, reunites him with Tom Hanks for the fifth time. It also stars another legendary Hollywood icon in Meryl Streep, who’s a Spielberg first timer. Set in 1971 and based on a true story, the film revolves around the Washington Post staff’s dilemma on whether or not to publish the Pentagon Papers, a top secret study of US involvement in Vietnam. The Pentagon Papers implicated several US administrations in lies and deception, rocking the American public’s trust in its government. Despite warnings of potential treason charges and jail, editor-in-chief Ben Bradlee (Hanks) and publisher Kay Graham (Streep) go to press anyway.

Stuck in the Past:

As a journalist myself, I was curious to see how Spielberg tackled this worthy subject matter. Two hours later, I can’t help but say I was disappointed. It’s a matter of taste, but I found Spielberg’s approach to be flat and disengaging. And yet, it is clearly addressing a timely pressing issue in a world where journalistic financial and editorial freedom is in peril.

But Spielberg does a much better job than director Tom McCarthy did in turgid 2015 Best Picture winner Spotlight, another film about a newspaper exposé. He tries all kinds of tricks to inject action and tension into a story that’s mostly just journalists talking. Some of those tricks, particularly those involving sound and music, are effective. Others involving characters throwing themselves in front of moving vehicles, or awaiting mystery phone calls that posit no real danger, are ham-fisted.

The Post’s narrative focus also seems off. Daniel Ellsberg (Matthew Rhys), the military analyst who leaked the Pentagon Papers, is introduced in the film’s first few scenes in Vietnam’s jungles. The soldiers he’s embedded with note his longer hair before he asks for a helmet – an unsubtle nod to the non-soldiers of the world who fight a different kind of battle. Initially, it seems like Ellsberg’s going to play a prominent role but he fades into the background. Considering the real-life Ellsberg was charged with the Espionage Act (and later exonerated), I’d argue he would have made for a more compelling main character.

But The Post is meant as a star vehicle for Hanks and Streep, who largely go through the motions here. They don’t stray from what they’ve comfortably done over and over in their careers. The physically and emotionally gruelling past ventures of Hanks (Philadelphia, Cast Away) and Streep (Kramer vs. Kramer, Sophie’s Choice) offer reminders of how nice and cozy they are in The Post. In fact, nothing edgy or provocative comes from the film as a whole. And whenever the characters say or do something that stands out, it reeks of older Hollywood propaganda. In 2018, it sticks out like a sore thumb.

A Publisher’s Dilemma:

Much of what’s good about The Post comes in the conflicts Graham must face. The tug and pull between Bradlee and Graham sheds light on the essence of how a newspaper, or any journalistic publication, operates. Bradlee is her conscience, adamant the Pentagon Papers see the light of day. But he is her employee, not responsible for the bottom line that guarantees the Post publishes anything at all.

Inheriting the newspaper after her husband’s suicide, Graham is a woman in a field dominated by men, and is treated as non-entity by the board she theoretically controls. The board members continually pressure her to shut Bradlee down and play it safe. She is also personal friends with Secretary of State Robert McNamara (an uncanny resemblance in Canadian actor Bruce Greenwood), a conflict of interest Bradlee questions when McNamara’s complicity in deception becomes evident in the Pentagon Papers.

These conflicts come to a head in the film’s final third and are set up in that straightforward Spielbergian way – how Graham handles these challenges determines what kind of person she is and how far she’s willing to go to fight for freedoms important for all of us.

But Where’s the Anger?

As solidly as it’s shot and framed, as lush and artful the sets and production, The Post’s passion is stilted, its message subdued by its old-fashioned smarm. A great example is a pivotal scene where Graham confronts McNamara about her intent to publish the Pentagon Papers. Here is a woman who finds out a close friend has secretly stated the US could never win in Vietnam, years before her son and sons of countless others risked their lives. Thousands more were killed and maimed. But where is her anger in that scene? Where is the film’s anger? Nowhere to be found.

Verdict: The Post is the latest solid, but unspectacular, entry in past-his-prime director Steven Spielberg’s filmography. If you can excuse a tepid first hour and a laboriously melodramatic style, The Post’s message about the importance of journalistic freedom and unsung heroes is timely and worth watching.

B-

Trailer: